31 July 2016

Birding Beijing

In the fun company of Paul Holt and Marie Louise, I have just made my 15th visit to Nanpu, a small town situated on the coast of the Bohai Bay in Hebei Province, China. At this time of year the outskirts of this unassuming settlement play host to one of nature’s most incredible spectacles – the migration of millions of shorebirds from their Arctic breeding grounds to their wintering grounds in the southern hemisphere, many travelling as far as Australia and New Zealand. It is truly awe-inspiring to see, and hear, flocks of shorebirds excitedly arriving on the newly exposed mud on the falling tide and there’s nowhere better in the world than China’s east coast to witness this stunning scene…. Just listen to ABC presenter Ann Jones and Chinese birder and good friend, Bai Qingquan, describe this phenomenon in this short clip from the excellent BBC World Service/ABC radio series.

A Google Earth image showing the location of Nanpu, in the Bohai Bay ©Birding Beijing

We enjoyed a brilliant two days with 33 species of shorebird logged, including flocks of long-distance migrants, many of which were still in fine breeding plumage, including Great Knot, Bar-tailed Godwit, Grey Plover, Sharp-tailed Sandpiper, the ‘Near Threatened’ Asian Dowitcher and even a single ‘Endangered’ Nordmann’s Greenshank. My poor quality video and photos simply don’t do justice to these birds.

Juvenile Asian Dowitcher, Nanpu, 28 July 2016 ©Birding Beijing

As we were travelling back to Beijing, I checked the news on my smartphone. The headline was about the Rio Olympics, a forward look to two weeks of celebrating the astonishing physical feats of the world’s best athletes – from 100m sprinters to marathon runners. The parallel with the shorebirds was striking. Take the Bar-tailed Godwit. One population of this species winters in New Zealand and flies, via the Yellow Sea, to Alaska and then, after raising its young, makes the return journey directly, a gob-smacking non-stop 11,000 km over the Pacific Ocean. According to scientists, this journey is the equivalent of a human running at 70 kilometres an hour, continuously, for more then seven days! Along the way, the birds burn up huge stores of fat—more than 50 percent of their body weight—that they gain in Alaska. And before they embark on this epic journey, they even shrink their digestive organs, superfluous weight for a non-stop 7-day flight. Try that, Usain!

The best athlete in the world: Bar-tailed Godwit or Usain Bolt? Bolt reaches speeds of around 48km/h, with an average of 38km/h, for under 10 seconds in the 100m sprint. The Godwit’s effort is the equivalent of running at 70km/h non-stop for 7 days! ©Birding Beijing

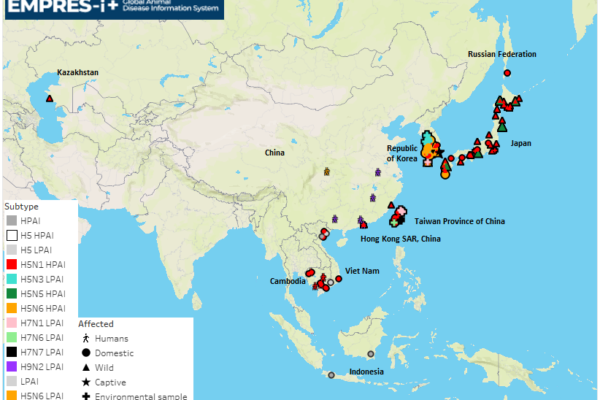

Sadly, the number of Bar-tailed Godwits successfully reaching New Zealand each autumn has fallen sharply, from around 155,000 in the mid-1990s to just 70,000 today. And the Bar-tailed Godwit is only one of more than 30 species of shorebird that relies on the tidal mudflats of the so-called Yellow Sea Ecoregion (the east coast of China and the west coasts of DPR Korea and RO Korea). The populations of most are in sharp decline, none more so than the charismatic but ‘Critically Endangered’ Spoon-billed Sandpiper.

So what is the reason for the decline? Scientists, including Prof Theunis Piersma and his team have, through years of painstaking studies, proved what many birders have long suspected – that the main cause of the decline is the reclamation of tidal mudflats along the Yellow Sea. Around 70% of the intertidal mudflats in this region have disappeared and much of the remaining 30% is under threat. If the current trajectory continues, the Yellow Sea will become a global epicentre for extinction.

The problem, in China at least, is a combination of local economics and national regulations. The coastal region of China is home to 40% of the country’s population, and produces roughly 60% of national GDP. Local governments receive much of their revenue through land sales and the land that demands the highest price is agricultural land close to major cities. However, to ensure China’s food security is preserved, there is a national regulation (the Law of Land Management) stipulating that there must be no net loss of agricultural land. So any farmland sold for development must be offset by land elsewhere being allocated for agriculture. The relatively cheap reclamation of mudflats is, therefore, a profitable way for Provinces to be able to sell high-value land for development whilst conforming with the “no net loss” rule by allocating much of the reclaimed land for aquaculture. In the absence of a law protecting nationally-important ecosystems, local priorities rule. And, although large-scale land reclamation projects, at least in theory, require national level approval, these rules are easily circumvented by splitting large projects into several, smaller, constituent parts. With a booming economy over the last few decades, resulting in high demand for land, the tidal mudflats are suffering death by a thousand cuts.

In RO Korea, it’s a similar story. Perhaps surprisingly, it’s DPR Korea’s relatively undeveloped coastline that could provide the last refuge for the dwindling populations of these birds.

So, what can be done? Ultimately, what’s needed is greater protection for, and more effective management of, nationally important ecosystems, including coastal wetlands, not only for migratory birds but also to avoid undermining China’s basic ecological security, such as providing fishery products, fresh water and flood control. That will require a combination of new laws, amendments to existing laws, regulations and greater public awareness. There is some great work on this, initiated by the Paulson Institute in partnership with China’s State Forestry Administration and the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, that makes some compelling recommendations.

In parallel to these recommendations, one idea is to secure nomination of the Yellow Sea Ecoregion as a shared World Heritage Site between China and DPR Korea and RO Korea. The concept is based on the Wadden Sea World Heritage Site, a so-called ‘serial’ nomination of linked sites across three countries. Initiated by The Netherlands and Germany in 2009, with Denmark joining in 2014, this World Heritage Site is based in large part on its unique importance for migratory waterbirds. Whilst World Heritage Site status wouldn’t mean automatic protection for the Yellow Sea Ecoregion, it would give it greater national and international recognition based on its significance for migratory shorebirds along the world’s largest and most important flyway. That must be a good thing.

More immediately there is much that must be done to raise awareness about the importance of these areas for migratory shorebirds, as well as local livelihoods – vital work if the conservation community is to have a chance of influencing local governments. Whenever I speak about migratory shorebirds in China, without exception, people are amazed by the journeys these birds undertake and they are enthused to do something to help. Most are simply unaware that the Yellow Sea coast lies at the heart of the flyway. The good news is that there is now an increasing number of local birdwatching and conservation groups in many of China’s coastal provinces engaging local governments and doing what they can to save their local sites. There are grassroots organisations in China working hard to promote environmental education, not only with schools but also the general public. And there is a growing band of young Chinese scientists studying shorebird migration along the Yellow Sea. These groups fill me with great optimism about China’s future conservation community.

Internationally, organisations such as BirdLife, including their superb China Programme team – Simba Chan and Vivian Fu – are working with groups such as the Global Flyway Network, the East Asian Australasian Flyway Partnership, as well as Professor Theunis Piersma and his dedicated team. Together, they are advancing the concept of the World Heritage Site with the UN, governments and local groups. At the same time, I believe it is incumbent on us all to be Ambassadors for these birds, to celebrate their lives and to do what we can to promote awareness about their incredible journeys.

The tidal mudflats of the Yellow Sea are one of China’s treasures, alongside the Great Wall, but they are in peril. Affording them robust protection and effective management is the highest conservation priority in east Asia and it’s a race against time.

Wouldn’t it be something if, alongside the rolling coverage of the Olympics, state TV and radio profiled the most impressive athletes of all – the shorebirds of the East Asian-Australasian Flyway?

The original post: https://birdingbeijing.com/2016/07/31/the-yellow-sea-the-highest-conservation-priority-in-east-asia/