With the recent outbreaks of AI in USA, speculative links to wild migratory birds that often appear with these outbreaks are being questioned for what they are – just speculation with no evidence. We do know these outbreaks occur in poultry farms with huge numbers of birds kept in unnaturally confined conditions. We also tend underestimate the scale and connectedness of the industry, with enormous numbers of chickens and other poultry being transported across countries and globally, from farms to markets. The risk of transmission is quite high and hence the focus on biosecurity measures, at farms, markets and transportation routes. Hopefully articles like this will help debunk the speculation of links to wild bird migration. Of course, ongoing research into AI is important and appropriate and targeted biosecurity measures can also help protect wild birds from domestic poultry AI outbreaks.

Mar 18, 2015

The notion that wild birds played a key role in bringing highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses from Asia to western North America and more recently to the Midwest has been implicit in government statements about recent outbreaks. But some wildlife disease experts are warning against jumping to easy conclusions.

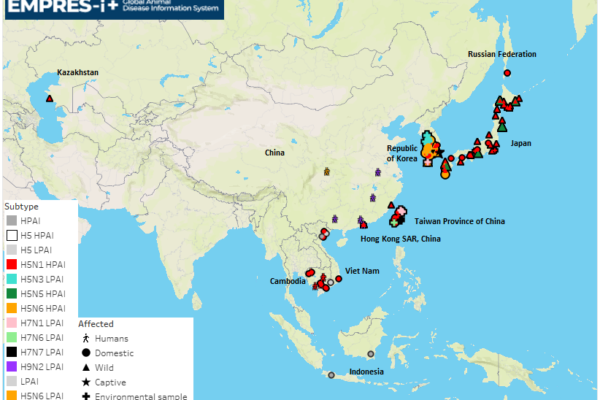

The story goes back to last November and December, when an HPAI H5N2 virus struck several poultry farms in southern British Columbia. Those outbreaks triggered increased surveillance for avian flu in the United States, and a matching virus showed up in December in a wild northern pintail duck in northwestern Washington state. At the same time, a Eurasian strain of H5N8 virus was found in a captive gyrfalcon in the same area.

The USDA reported that the Minnesota, Missouri, and Arkansas H5N2 isolates looked more than 99% similar to the Washington pintail duck virus. LHG Creative Photography / Flickr cc

Subsequently the H5N2 virus surfaced in several backyard poultry flocks and wild birds in Oregon and Idaho as well as Washington. And this month it popped up on a western Minnesota turkey farm and shortly afterward on two Missouri turkey farms, an Arkansas turkey farm, and a backyard flock in Kansas. The H5N2 strain is described as a product of mixing (reassortment) between the Eurasian H5N8 virus and native North American avian flu viruses.

In a Mar 11 announcement about the Arkansas outbreak, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) said, “These virus strains can travel in wild birds without them appearing sick. People should avoid contact with sick/dead poultry or wildlife.”

Last week the USDA reported that the Minnesota, Missouri, and Arkansas H5N2 isolates looked more than 99% similar to the Washington pintail duck virus, based on partial genetic sequencing of the virus’s hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins. The apparent implication was that migratory birds may have brought the virus to those states.

Wild bird chase?

But not so fast, say experts like David Stallknecht, PhD, of the University of Georgia’s College of Veterinary Medicine, and Michele Carstensen, PhD, wildlife health program supervisor in the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR). They point out, among other things, that migratory birds don’t migrate from west to east or from north to south in late winter.

“This could all have been from wild birds—nobody can say it’s impossible,” said Stallknecht. “But we do need some proof. . . . People seem to be willing to accept things without a whole lot of proof.”

He said it is unknown how the H5N8 strain that gave rise to H5N2 reached North America. Noting that the H5N2 outbreaks in British Columbia marked the “index case” or first appearance of the virus, he said, “How much proof do we have of wild bird involvement with that virus in North America? None.”

Referring to the mixing of H5N8 with North American viruses, he said, “Why do we make the jump to wild ducks to explain this? Reassortment could also occur in a backyard flock of domestic ducks after a more direct introduction [of H5N8] via people.” He suggested that travelers could possibly have brought the virus to Canada from Asia.

He cautioned that this is “pure speculation,” but added that the idea that wild birds introduced the parental H5N8 virus to North America is also speculative. “It is based on circumstantial evidence that is rapidly becoming accepted dogma.”

Carstensen said the notion that wild birds could have brought the H5N2 virus from Minnesota to Missouri is “beyond me. . . . They [migratory birds] go from south to north this time of year.” Arkansas and Kansas, on the other hand, are close enough to migratory-bird wintering grounds to make a connection with wild birds more plausible, she added.

There could be “totally different causes” for the outbreaks in Minnesota and the more southerly states, Carstensen suggested.

Two positive tests in Minnesota

She and her colleagues have been testing fecal samples from wild birds found near the site of the outbreak in western Minnesota. A total of 148 samples, in three batches, have been tested for the presence of any avian flu virus. Only 2, both from mallards, tested positive, but the viral subtypes were not determined, she reported today. The samples have been sent to a USDA lab for the subtype determination.

If the viruses turn out to be H5 or H7 strains, their pathogenicity will be determined, which would take several weeks, Carstensen said. She noted that a number of H5 and H7 viruses were found in Minnesota wild birds in recent years, but they were all of low pathogenicity.

Even if wild birds did bring the H5N2 virus to Minnesota, she said, “It still has to get from the birds to the farm. The birds don’t go there; it would have to be people or vehicles. The farm doesn’t have any reports of waterfowl there at all.”

Stallknecht said that whether the source of the virus was wild birds or human activity makes no difference in how to respond to and control the virus, but it does make a difference in other ways.

“Biosecurity is everything now, regardless of the source,” he said via e-mail. “With regard to future risks for introductions of exotic viruses (flu or otherwise), however, it might be nice to know what really happened here.”

See also:

Mar 11 CIDRAP News story on Arkansas outbreak

Mar 6 USDA report to World Organization for Animal Health on Minnesota H5N2 outbreak

Mar 10 CIDRAP News story on second Missouri outbreak

USDA list of recent HPAI detections in wild birds

USDA avian flu update page with summary of recent findings

Reprinted with permission from the Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy, © 2015 Regents of the University of Minnesota. The original article is available here.