Article prepared by Vladimir Pronkevich1, Konstantin Maslovsky2, and Philipp Maleko3,4

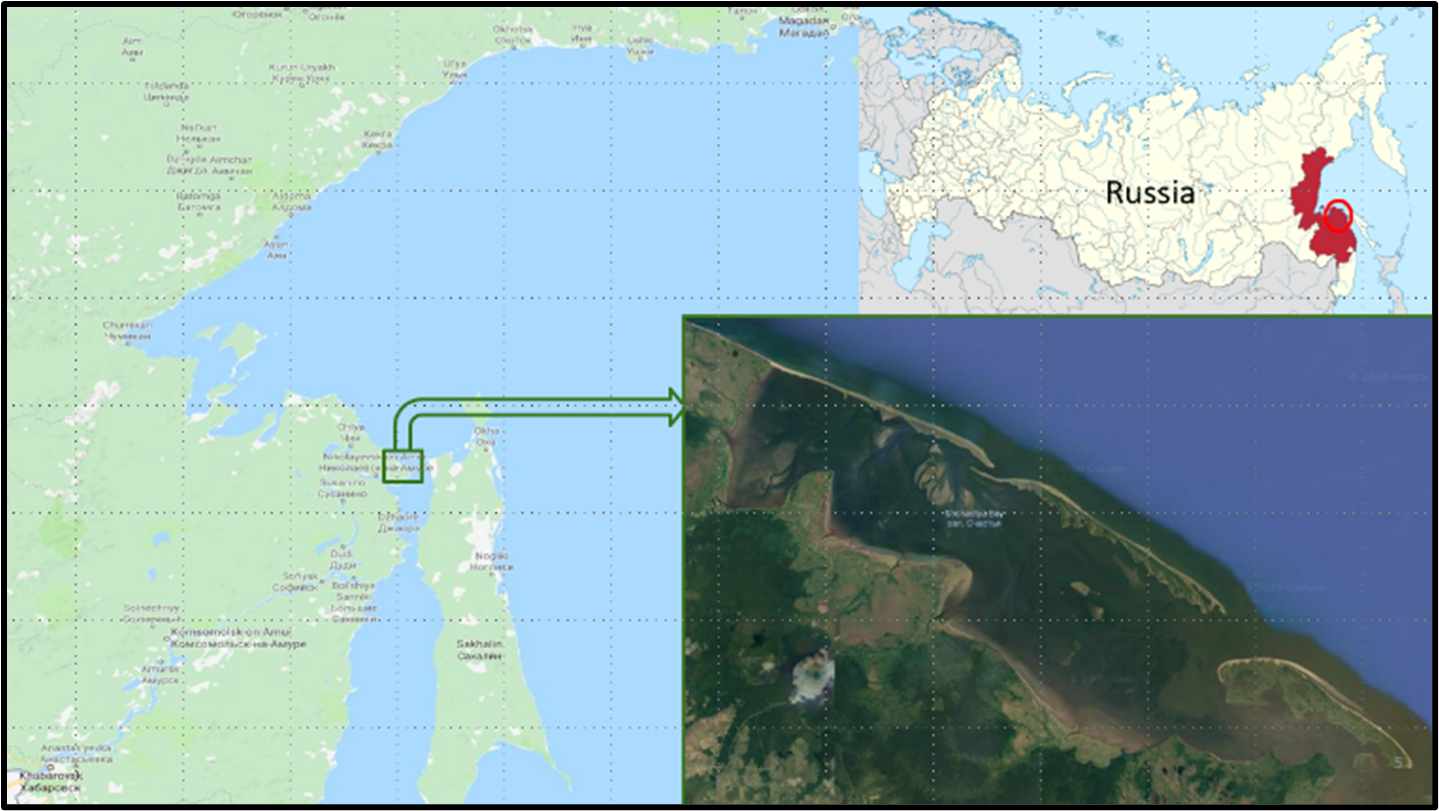

During the summer of 2021, we continued studying the breeding ecology of Endangered Nordmann’s Greenshank (Tringa guttifer) and ubiquitous Common Redshank (T. totanus) in Schaste Bay, Khabarovsk Krai, Russian Far East (Fig. 1). The field season, sponsored by the Wildlife Conservation Society (Arctic Beringia Program based in Fairbanks, Alaska and the offices based in Vladivostok and Terney, Russia), lasted from 14 June to 22 July – encompassing the nesting, brood-rearing, and migratory periods. Our main objectives were to 1) find greenshank and redshank nests, 2) tag 10 birds of each species with 3.5 g Nano GPS tracking devices developed by Druid Technology Co., Ltd. 3) resight birds banded in previous years, and 4) survey for breeding and migrating Nordmann’s Greenshanks at key sites. We hope our research sheds light on the breeding ecology of enigmatic Nordmann’s Greenshank throughout their breeding grounds and helps designate Schaste Bay as a regional Nature Park, a protect area designation equivalent to IUCN Category VI. We also hope by tagging the species with tracking devices we can better understand their migratory ecology, and ultimately help protect sites along the species’ migration and within overwintering grounds.

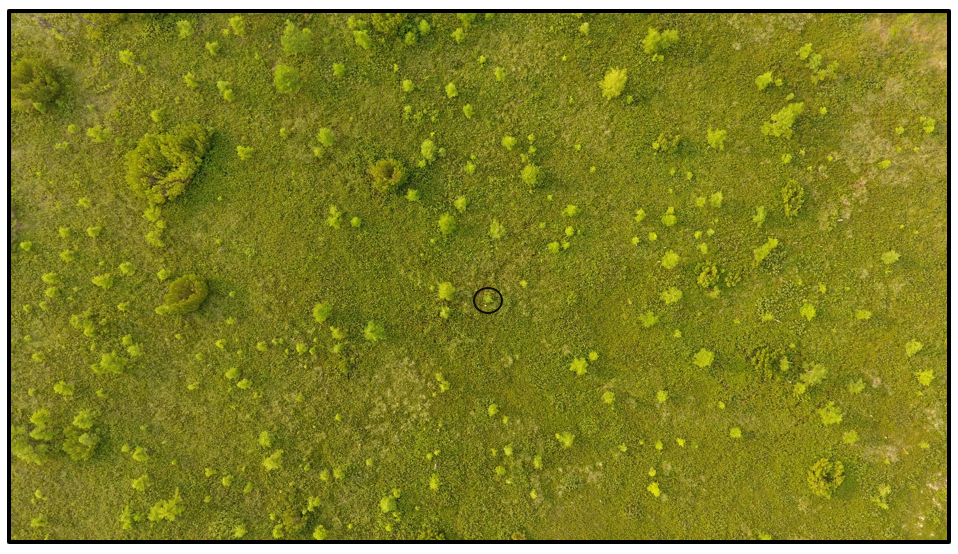

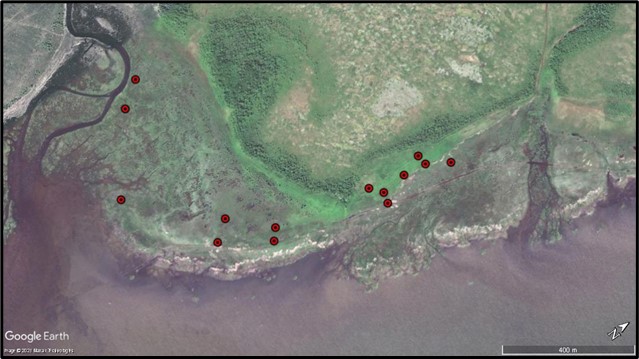

From mid to late June, we searched for Nordmann’s Greenshank nests throughout the hummocky inland bog of northwestern Schaste Bay. With the help of binoculars and a spotting scope provided by Wader Quest (England and Wales, U.K.), we were successful in finding four nests. All four nests were situated on the ground- three on hummocky sections of the inland bog and under sapling larch trees (Fig. 2), while the fourth was on the edge of inland bog and larch forest fragment and at the very base of a large larch. Fortunately, the eggs from all four nests hatched and chicks were successfully led to brood-rearing areas by tending adults. Although it is still undetermined which variables – climactic, behavioral, individual, or environmental – influence where greenshanks build their nests, we can confidently state that the species nests on the ground more frequently than previously known and that their nesting plasticity is wide. This finding also hints that nesting habitat for Nordmann’s Greenshank’s in Schaste Bay is abundant (Fig. 3) and that the main factors limiting the species population are likely on their migration and overwintering grounds rather than in the Russian Far East. In 2021, we also found 14 Common Redshank nests on the coastal meadow of our study site (Fig. 4), bolstering our power of inference regarding the possible impacts of all-terrain vehicles on redshank nesting habitat.

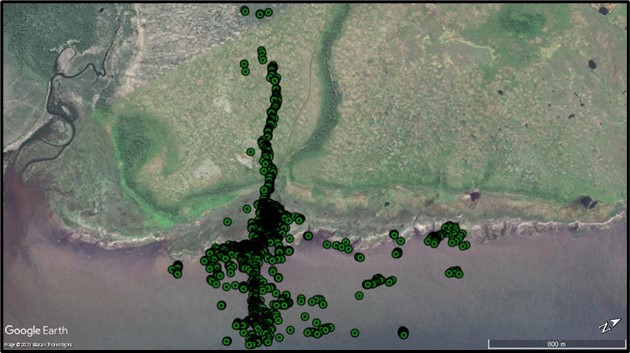

Besides finding nests, our main objective was tagging birds with GPS tracking devices. We accomplished our goal and tagged 20 individuals – 10 greenshanks and 10 redshanks. The 1st East Asian-Australasian Flyway Shorebird Science Meeting Tracking Device Competition awarded us 10 of the tags and 10 additional tags were generously donated to the project by Dr. Jimmy Choi, Assistant Research Professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, China. The tracks are already providing rather interesting results. For example, the points collected from greenshanks captured right after chicks hatched reveals how adults transition with their brood from the bog to brood-rearing grounds on the coastal meadow and intertidal flat (Fig. 5). We are now patiently hoping our tagged birds will stop in coastal China where our colleagues, using HUB Bluetooth receivers, can capture data from these birds and help us understand which sites greenshanks hop along during migration and their habitat use within stopover sites. We are also looking forward to the 2022 season, when we hope to find tagged birds, download data to help us identify overwintering sites and understand migratory strategies, as well as recapture birds to remove tags.

Resighting of birds banded during the 2019 and 2020 field seasons was also successful, again in part thanks to equipment provided by Wader Quest. We located 6 of 9 greenshanks: 4 of 7 banded in 2019 (Fig. 6) and both birds banded in 2020, and 16 redshanks: 8 of 17 banded in 2019 and 8 of 15 banded in 2020. This return rate reveals both species have relatively high site fidelity and further emphasizes the need for protecting important breeding grounds.

A critical part of the 2021 season was surveying for breeding and migrating Nordmann’s Greenshanks throughout different sections of Schaste Bay (from the Petrovskaya Spit to the Iska River in the northwest, and the estuaries of Komel, Avri, and Chorniy in the southeast), as was done in previous years. This is important to establish a baseline dataset on the species’ population trend throughout its breeding grounds. During the first weeks of July we observed migratory groups from 30 to 90 individuals, roughly representing 200 birds. We also observed 57 breeding birds, representing roughly 37 pairs. This highlights that Schaste Bay warrants being designated as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance as it supports > 10% of the global population of Nordmann’s Greenshanks, and further underscores the need to establish Schaste Bay as a protected area.

Besides ornithological research, we continued strengthening relationships with individuals in the local community. These relationships are crucial for us to understand the various socio-economic, political, and cultural factors putting pressure on the people and wildlife of Schaste Bay, and for us to identify the optimal strategy to designate Schaste Bay as a protected area while ensuring the livelihood of the local communities.

We thank Jonathan C. Slaght for his steadfast dedication to the project and for his role in a success 2021 field season.

Figure 1. The location of Schaste Bay in Khabarovsk Krai, Russian Far East.

Figure 2. A Nordmann’s Greenshank nest, found in 2021, situated under a sapling larch tree on the hummocky inland bog of northwestern Schaste Bay. © Philipp Maleko.

Figure 3. A drone image showing the location of a Nordmann’s Greenshank nest (circled) and the plethora of suitable nesting habitat in its immediate vicinity. © Vladimir Pronkevich

Figure 4. Distribution of Common Redshank nests on the study site’s coastal meadow.

Figure 5. GPS points, collected from a Nordmann’s Greenshank tagged on while with its brood still on the inland bog, showing the transition from inland bog to coastal meadow and then its movement with the brood throughout the brood-rearing areas.

Figure 6. A Nordmann’s Greenshank banded in 2019 – red engraved flag (P1) with color bands red (faded to white) over dark green resighted on the hummocky inland bog in 2021 during the nesting period. © Philipp Maleko.

Author’s affiliation:

1Khabarovsk Federal Research Center, Institute of Water and Ecology Problems, Far Eastern Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences.

2Federal Scientific Center of the East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity, Russian Academy of Sciences.

3Florida Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, University of Florida, Gainesville.

4Wildlife Conservation Society, Arctic Beringia Program, Fairbanks, Alaska.

Check the 2020 EAAFP Small Grant Fund article “Studying the breeding ecology of Endangered Nordmann’s Greenshank and Common Redshank in Schaste Bay, Russian Far East for enacting efficient conservation planning” by the team.