Baer’s Pochard Aythya baeri was formerly a relatively common and widespread duck in Asia, although it has possibly not been abundant for a long time, and in fact there has never really been a good understanding of its population size. This species has always been somewhat overlooked by ornithologists, partly owing to difficulties visiting and surveying the areas in which it occurs. In addition, uncertainty over the accuracy of identification of some historical records also clouds our understanding.

However, whilst historical and recent uncertainty remains, there can now be no doubt that this species has undergone a catastrophic decline in recent years and is on the brink of extinction in the wild. Without an urgent response from the conservation community, this species is very likely to be lost in the near future.

Evidence of former abundance comes from the 1910s when La Touche found it to be “extremely abundant” on migration on the coast of Hebei province in China, though migration studies there in the late 20th century found it to be a scarce passage migrant, indicating that a substantial decline took place during the 20th century. It has also been described as “common” or “quite numerous” by a number of other authors referring to Japan and China (see Threatened Birds of Asia for full details), and numerous counts of hundreds of individuals exist for countries within the core of its former wintering range, including Bangladesh, Myanmar and Thailand.

By the late 1980s it was thought to number no more than 25,000 individuals, possibly fewer, and was recognised as being in decline; as a result it was added to the IUCN Red List in 1994 as Vulnerable. There it remained until 2008, when it was uplisted to Endangered, shortly followed in 2012 by uplisting to Critically Endangered, followingan assessment that strongly suggested a population of fewer than 1,000 individuals.

Since being listed as Vulnerable very little new information has come to light, other than a fairly wide acceptance that it has largely disappeared from some countries in the south of its wintering range, including Thailand and Bangladesh.

Current status

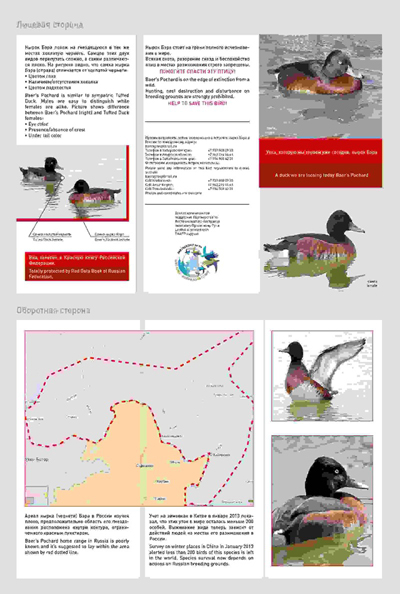

Leaflet to report sightings of Baer’s Pochard in Russia. EAAFP supports surveys in Russia in 2013. © EAAFP

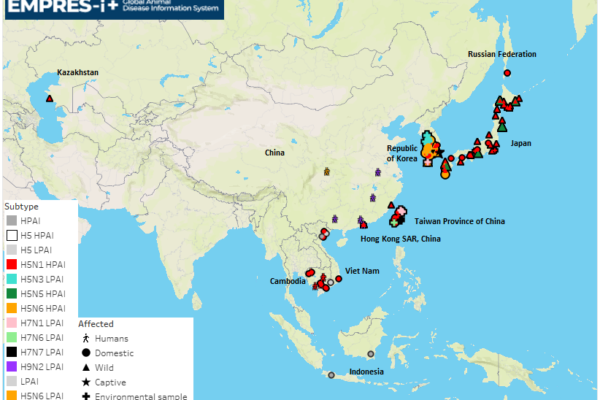

Following the revised status assessment and uplisting to Critically Endangered, more concern has focused on this species.However, it appears that the status of Baer’s Pochard has further deteriorated significantly in just the past two years.Wang et al. (2012) documented that in the winter of 2010/11 there were still some significant flocks of birds in the central Yangtze floodplain, with 90 at Hong Hu in November and 131at Liangzi Hu (both Hubei) in January and 760 at Wuchang Hu (Anhui) in November and 230 at FengSha Hu (Anhui) in February. However, in the past two winters records of Baer’s Pochard have been few, with the only double-figured count being 26 birds at Poyang Hu in November 2012. This is despite two concerted efforts to locate birds in 2012/13. The first of these involved a detailed study of Liangzi Hu, with comprehensive monthly counts undertaken between October and March, which turned up a single record of two birds. In addition, a wide ranging effort was made to census as many sites as possible within the winter range, particularly in the central and lower Yangtze floodplain, during January 2013. Whilst coverage was incomplete, in all around 40 sites were surveyed in China and a maximum of just 45 birds was recorded. A small number of key sites checked in Bangladesh and Myanmar all returned nil counts.

Recent breeding records are even fewer in number. In 2012 there was a confirmed breeding attempt in Hebei, and an unconfirmed report of four pairs at a site in Shandong. Both sites are to the south of the recognised breeding range and pose interesting questions about whether the range has historically extended that far south. No breeding records were received from the core breeding range (NE China and neighbouring parts of Russia) at all during 2012, despite some searches undertaken at Lake Khanka and other Russian wetlands during which the only observation was of two individuals at Lake Khanka in August. Further searches are currently taking place in 2013, partly funded by EAAFP.

All of this is a far cry from the number known to exist as recently as just two years ago, and overall it is now clear that Baer’s Pochard is becoming an extremely difficult bird to locate anywhere in its range, even during dedicated searches. The statement by Wang et al. (2012) that “we fear that the global population is now less than 1,000 individuals and could be very much lower than this”, seems almost certain to be true, and on current evidence there could be fewer than 100 individuals remaining in the wild.

What are the threats?

Almost nothing is known about why Baer’s Pochard has apparently declined so rapidly. We do know that many wetlands within its range are now severely degraded, particularly within the core winter range, and this is likely to have contributed to the decline even if it is not the main factor. However, no other sympatric freshwater ducks seem to be undergoing such rapid declines, so it would seem that there is something specific about Baer’s Pochard that is also contributing to its decline. It is important to note, however, that data on other more numerous ducks, especially their population trends, remains limited, despite recent significant improvements, and thus it is possible that other duck species are also undergoing significant declines that currently remain undetected because they are still relatively numerous.

Habitat loss and degradation in breeding areas seem less likely to be a major cause of decline, simply because the breeding range has relatively low human impact, but little information has been collated on this to date. Surveys and site assessments in breeding areas are urgently needed, and some will be carried out in 2013.

Another key threat faced by many Asian ducks, which likely includes Baer’s Pochard, is the unsustainable harvesting of individuals, although as with habitat loss and degradation it is currently difficult to quantify the scale and relative importance of this. However, it could be significant, particularly in China where the illegal poisoning and trapping of waterbirds is widespread.

Whilst shooting may have been a significant problem in the past, gun use is now heavily controlled in China and it would appear that other methods are the primary means of harvesting waterbirds.

Few other threats appear as obvious potential causes of the decline, but so little information is available that it is currently impossible to be certain whether other factors are at play here or not. Given this, diagnosis of the decline is likely to take time, and in fact it may already be too late for this.

What can we do about it?

Currently, the lack of knowledge about the species and the factors causing its decline severely limit our ability to confidently propose a robust conservation response. There are only 2-3 sites now known to regularly support the species, either during the winter or breeding season, and numbers at all of them are low and declining at an alarming rate.

Certainly the population size and decline rate of Baer’s Pochard, coupled with the inherent difficulties – and hence time lags – in stabilising the population, mean that its extinction in the wild appears to be imminent. In a close parallel with Spoon-billed Sandpiper, the rapid acceleration in decline in a population that was already moderately small has meant that the species has gone from moderate concern to virtually extinct before a conservation reaction has had time to develop.

There is a considerable likelihood that the keys to saving Baer’s Pochard are improved management of large central Chinese wetlands, and possibly other wintering sites outside this region, and a significant reduction in harvesting activities, but these are both large complex problems that will themselves take much time and effort to resolve in a way that could have an effect at a population scale. Clearly there are ongoing efforts to reduce wetland degradation and improve site management in China, but these are not particularly targeted at Baer’s Pochard sites, and in any case the species has reached the point where emergency close-order management is almost certainly needed.

If something is going to be done in the short term, further surveys and searches for the species are an obvious starting point. It is important to note that although there has been some effort at locating Baer’s Pochards during the past 12 months, coverage was far from complete and there remains the possibility that more birds exist than were counted. Furthermore, even though coverage was good at wintering sites in the central and lower Yangtze floodplain, some of these sites are vast and very difficult to survey comprehensively. Thus even at surveyed sites some birds may have remained undetected, although the likelihood of significant numbers remaining uncounted seems low. One other explanation for low counts in the historical range is that the winter range of the population may have shifted. This phenomenon is known to be happening with other migratory waterbirds that breed in arctic and boreal zones and winter in temperate regions, and so there remains a possibility that there could be new wintering areas for Baer’s Pochard further north than previously recorded.

There were two sites (in Hebei and Shandong) where Baer’s Pochard most likely bred in 2012. As ducks are quite amenable to close-order management, actions at these sites that ensure breeding birds are protected and able to breed successfully are crucial. These actions could include strict zonation and minimisation of disturbance, habitat protection at all times of the year, nest protection, and potentially translocation and boosting of reproductive output by direct intervention.

The global captive population of Baer’s Pochard appears relatively healthy. However, an important issue to resolve is the genetic purity of this captive population, about which there are some concerns, which may indicate a much smaller pool of birds for a captive breeding programme that previously thought.

So the situation facing Baer’s Pochard is undoubtedly bleak at the moment, but no matter what eventually becomes of this species we need to ensure the very clear message from its plight is heeded. Whilst it may already be too late to save Baer’s Pochard from extinction in the wild, this story is undoubtedly another strong warning about the health of Asian waterbird populations and the wetlands that support them. In recent years much has rightly been said about the state of shorebird populations and intertidal habitats in the East Asian-Australasian flyway, highlighted by the plight of the Spoon-billed Sandpiper. However, what Baer’s Pochard tells us is that the situation may be just as serious for inland freshwater species, such as many ducks.

Experts will gather at the EAAFP Meeting of Partners in Alaska in June 2013 to consider developing a Task Force for Baer’s Pochard and formulating an Action Plan for its conservation. It is clear immediate actions need to be undertaken in the very near future if the species is to be saved. Visit for more information