Posted on: January 22, 2014

Author: Amorn Liukeeratiyutkul, Gawin Chutima & Philip D. Round

Report by Bangkok Post

Greater efforts will be needed, both at home and abroad, to prevent the extinction of a plucky little bird which breeds in Russia and then makes a marathon annual migration to Southeast Asia

Does it matter if a bird goes extinct?” someone asked not long before the opening of an international monitoring workshop on the spoon-billed sandpiper organised by the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand. The gathering was held in conjunction with BirdLife International, a global partnership of conservation organisations with more than 3 million members and supporters in 121 countries

On Oct 26 last year, the first spoon-billed sandpiper (Eurynorhynchus pygmeus) of the season reached its winter home at Khok Kham, on the shores of the inner Gulf of Thailand at Samut Sakhon province. A handful of others seen since bring the total for the season up to seven so far, and more are expected.

The very first sighting of a spoon-billed sandpiper in this country was recorded in January 1984 at Khao Sam Roi Yot National Park, Prachuap Khiri Khan province. Thirteen more were seen in Pattani Bay in the far South, that same year.

Alas, none have been spotted in Pattani since then. But the exciting news is that these birds have been spied every year since 1999 on Bangkok’s doorstep, in the single greatest coastal wetland in the Kingdom, the inner Gulf of Thailand.

There, more than 235km2 of tidal flats and 500km2 of onshore salt-pans and low-intensity prawn-capture ponds has been declared an Important Bird Area.

It extends from Chon Buri province westwards past Samut Prakan and Bangkok to Samut Sakhon, Samut Songkhram and Phetchaburi provinces. Each year it becomes a temporary home to between 10 and 20 spoon-billed sandpipers _ possibly as much as 5% of the global population of this shorebird which has been listed as critically endangered.

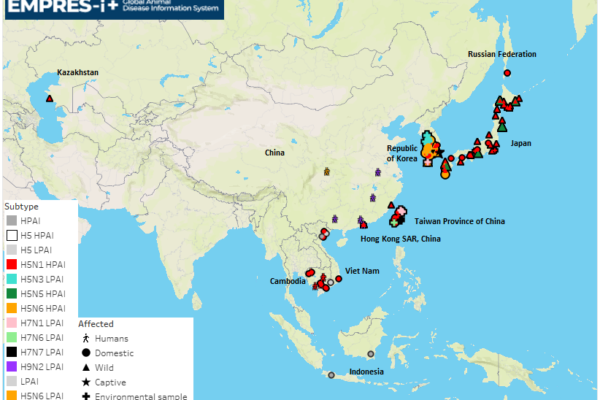

The Gulf of Thailand is a key area lying on the so-called East Asia-Australasian Flyway, a major waterbird migration route. The flyway extends from the Arctic Circle in Russia and Alaska, southwards through East and Southeast Asia, to Australia and New Zealand in the south, crossing 22 countries in all.

The spoon-billed sandpiper, one of the rarest of the birds which use this flyway, was recognised as critically endangered in 2008 by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The step was taken because the already extremely small population of this species was undergoing a further very rapid decline, due to a number of factors _ habitat loss in its breeding, passage and wintering grounds, compounded by disturbance, hunting and the effects of climate change. Fledging success and juvenile recruitment are very low, leading to fears that the population is ageing rapidly.

Action is urgently required to prevent the extinction of this species. The population of the spoon-billed sandpiper was estimated in 2009/10 at a mere 120 to 200 breeding pairs, roughly equivalent to between 240 and 400 mature individuals, with perhaps just 360 to 600 individuals, with perhaps just 360 to 600 individuals in total, although even this figure may be over-optimistic.

After breeding between June and August in the coastal moss and lichen tundra of Chukotka, in farthest northeastern Russia, the “spoonies” brave a journey of 8,000km to spend at least six months (October-March) in the radically different tropical environment of the Land of Smiles. Thailand’s inner Gulf is still rich in feeding areas and food resources. When the tide is high during daylight hours, the spoon-billed sandpipers and countless thousands of other shorebirds _ more than 50 species in all, including the similarly threatened Nordmann’s greenshank (Tringa guttifer) _ and larger waterbirds such as the black-faced spoonbill (Platalea minor) feed and rest around the margins of shallow, water-filled salt-pans. In the late afternoon and during the night they fly out to enjoy the bounty of the fertile mudflats which are exposed at low tide. Small aquatic worms, molluscs and tiny crustaceans are their principal foods.

There is no conflict between the lifestyles of shorebirds (also known as waders) and those of the coastal salt-farmers and inshore fishermen: both birds and people have a vested interest in the maintenance of our rich coastal resources. As a result, shorebirds are mostly safe and unmolested in Thailand, which is one of very few countries in Asia where sightings of spoon-billed sandpipers may be guaranteed.

For the hundreds of European and North American nature tourists who visit Thailand’s shores each year, spotting a spoon-billed sandpiper is the main highlight of their stay.

Elsewhere, the spoon-billed sandpiper is much more wary and difficult to observe. The hunting of shorebirds for food remains a major threat to the spoon-billed sandpiper and other species in several other parts of Asia. Farther north along the flyway, in countries such as Japan, Korea and China, people have already filled in (“reclaimed”) and destroyed large areas of formerly fertile coastal mudflats for use as building land _ and further developments are planned. This has deprived globe-spanning migratory waders of the staging areas they need for rest and stocking up on food before continuing their long and arduous journeys.

All these threats have taken their toll upon the spoon-billed sandpiper, the global population of which is thought to have declined by as much as 90% in the past 30 years. As recently as winter 2003/04, more than 20 spoon-billed sandpipers were spotted in the Gulf of Thailand, with 16 individuals seen at Ban Pak Thale and four more at Khok Kham. This is more than twice the number sighted in the inner Gulf of late.

This spoon-billed sandpiper, spotted in Thailand last December, has a ring and leg flag tagged by a Russian scientist. The bird has made a journey from the northeast of Russia to the Kingdom. © Bangkok Post.

Coordinated efforts by BirdLife International partners along the East Asian-Australian Flyway are now in place to halt this precipitous decline which, if allowed to continue, could lead to the extinction of spoonies in a decade or two from now. Russian researchers and specialists from the UK’s Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust are taking steps to minimise predation and enhance the survival of spoon-billed sandpiper chicks in their Arctic breeding grounds. This year, 16 hand-reared fledglings and eight adults were marked with uniquely inscribed plastic leg flags and were protected from Arctic foxes and other predators until they were able to fly. Birdwatchers are being asked to report all sightings of spoon-billed sandpipers along the flyway. Additionally, Korean and Chinese ornithologists and conservation bodies are lobbying their governments to halt the loss of coastal mudflat staging areas, while in both Myanmar and Bangladesh, NGOs are successfully reducing the hunting of shorebirds through the provision of alternative livelihoods.

Here, in the Gulf, the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand (BCST) has been closely monitoring the species since 1995 and working with local communities on the assumption that appropriate tourism is a powerful incentive to conserve this bird’s wintering areas. The society is also preparing for a midwinter census of spoon-billed sandpipers. The hope is that increased coverage, led by local BCST watchers _ such as Suchart Daeng-phayon, a Samut Sakhon salt-farmer, and Seri Manich, a Phetchaburi fisherman, both now turned full-time conservationists _ may yet reveal the existence of more spoon-billed sandpipers.

The conservation and protection of the inner Gulf of Thailand as a natural buffer against flooding for the of Bangkok or Phetchaburi, Samut Songkhram and Samut Sakhon, is urgent and unavoidable. This can best be done through supporting low-intensity uses such as salt-farming and sustainable inshore fisheries that do not damage biodiversity.

Future generations will surely curse us if we do not act now to halt urban sprawl, limit the spread of industrial aquaculture and conserve the wonderful watery wilderness on our doorstep.

Original Link: https://www.bangkokpost.com/life/social-and-lifestyle/390799/making-the-welcome-warmer