Korean visitors with staffs from WWF-Hong Kong and students in Hong Kong in front of Mandala © Eugene Cheah/EAAFP

EAAFP Secretariat

Shinhye Han, Intern

At the 2017 Black-faced Spoonbill International Workshop held last November, Incheon and Hong Kong had the opportunity to collaborate by sharing their policies in order to improve the conservation of Black-faced Spoonbills and their habitats. In an effort to strengthen the relationship, a group of conservationists from Incheon, including Black-faced Spoonbill Network, BFS Small School, and students, visited three wetlands in Hong Kong from January 20th to the 23rd. Tomoko, Eugene, and I joined the trip from the EAAFP Secretariat.

On the way to our first destination, the Hong Kong Wetland Park, the weather was so warm and nice like the beginning of summer. To my surprise, we were welcomed by Black-faced Spoonbills. On a lake, right next to the window of the cafeteria in the Wetland Park, were sitting a couple of Black-faced Spoonbills and Great Cormorants closer than ever.

In the middle of the city with numerous buildings around, the Wetland Park is an attraction for citizens © Eugene Cheah/EAAFP

We took a guided tour of the Hong Kong Wetland Park, which had created different environments depending on the species living on each area giving an impression that people have taken into account environmental conservation since its planning stage. Another charm of the park was that we could see many people enjoying their holiday with friends or family. The Wetland Park was not just a sanctuary, but also an ordinary place for them.

Meeting Black-faced Spoonbills had a significant meaning particularly to us who assembled for their conservation. Raymond, the guide of the Wetland Park, told us that given Hong Kong is a small-sized city, the fact that about 10% of 4,000 individuals winter at Hong Kong is evidence of the suitability of the city as a wintering site. One of the scientists’ concerns is, however, that Black-faced Spoonbills have recently shown an inclination to gather in two areas; Hong Kong and Taiwan, which means destruction or infection in any one of them might have a serious impact on the conservation of the species.

Mangroves inside Gei Wai in Mai Po provides small ecosystem for underwater life and birds © Shinhye Han/EAAFP

Our next destination was Mai Po – Inner Deep Bay [EAAF003]. We met Kitty, Nicole, and Yee from WWF-Hong Kong and three local students. Each district, including Gei Wai, reedbed, and mangrove forests, has been managed separately for their unique conservation purposes. Gei Wai in Mai Po was the last Gei Wai left in Hong Kong and functioned as a good food source for waterbirds as mangroves therein fed on shrimps, clams, and fish living inside. WWF-Hong Kong has managed the area by checking its water quality and controlling the water level on a regular basis.

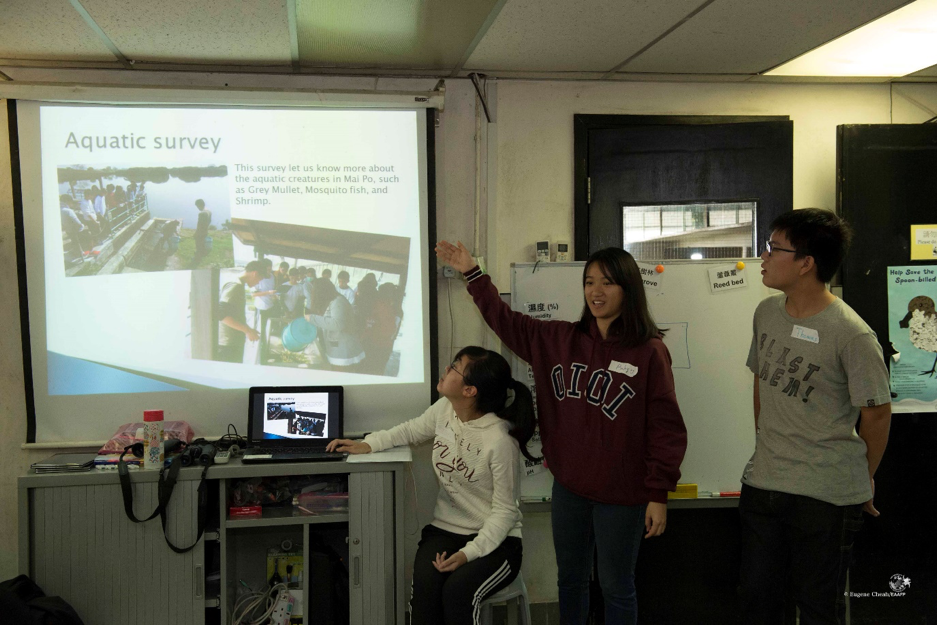

Hong Kong students giving a presentation about their activities as a part of citizen science © Eugene Cheah/EAAFP

After taking a look around Mai Po, we had an exchange session between Korean and Hong Kong students, introducing their conservation activities to one another. The most impressive was that Hong Kong students took part in citizen science that promoted raising public awareness and researching altogether by encouraging citizens to conduct ecological surveys. They had participated in Biodiversity surveys themselves including water quality and bat survey, making a contribution in creating an ecology map in Mai Po. Such an achievement would not have been possible without the contributions of the people of Hong Kong to this ecological research in which data plays such an important role. Korean students’ presentations were similar in that they also looked into the surrounding environment, but they conducted a variety of activities respectively in the school clubs or NGOs to which they belonged. One of them investigated swallow’s nests, and another did rice farming. Sharing what they felt from each other’s activities afterward, everybody was able to feel a connectedness that we were all here for environmental conservation. We drew and attached our messages on Mandala wishing for the better environment together.

In addition to the guided tour of Mai Po, we joined two surveys; Mammal survey and Mangrove survey. WWF-Hong Kong has figured out the current state of some mammals which were difficult to observe, such as the Leopard Cat and the Small Indian Civet, with infrared cameras. Particularly in case of the Eurasian Otter, even though it had been regarded as almost extinct in Hong Kong, it was captured by an infrared camera in March 2016. We had the opportunity to change the batteries of a camera and check the pictures it had taken. During the Mangrove survey, we learned how each mangrove species has adapted to tough conditions. For instance, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza has developed a dropper of pointed shape so that it could stand firmly in the intertidal zone flooded by tides every day. Pneumatophores, also known as pencil roots, of Avicennia marina have been evolved to grow vertically up to the air out of the soil because it was hard for underground roots to breathe in waterlogged soil.

Pied Avocets in Long Valley © Eugene Cheah/EAAFP

The third wetland was Long Valley, managed by the Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (HKBWS), where we could learn the history of the site and their efforts toward its conservation. Interestingly, the Hong Kong government, NGOs, and locals have cooperated on making Long Valley what it is. One of their key strategies was diversifying species of crops depending on the season so that many creatures were able to live in the area. The number of bird species has increased accordingly, from 81 in 2005 to 311 in 2017. As we have some target species such as Black-faced Spoonbills and Spoon-billed Sandpipers, HKBWS also has target species; Yellow-breasted Bunting, Critically Endangered species on the IUCN Red List. The population for this creature has drastically decreased due to hunting, because it was believed to boost sexual vitality and clear the body of toxins. They have carried on awareness-raising campaigns for Yellow-Breasted Bunting. Afterwards, we took an hour long bird watching walk in Long Valley. For a brief period, we watched over 30 species including Pied Avocet, Long-tailed Shrike, Olive-backed Pipit, Scaly-breasted Munia, and Yellow Wagtail. Hong Kong and Incheon shared so many species together, like Black-faced Spoonbills.

The four days of the trip in Hong Kong can be described as “coexistence and cooperation.” What I felt whenever I looked through my camera lens was that the wetlands and city were in the same frame. What awkward and enlightening moments. Coexistence of conservation and development is achievable, and for this, cooperation of people living in the area is crucial. All three wetlands in Hong Kong delivered the message in their own way. Historically, development has often been used for justifying the destruction of the environment, whose image was the very opposite of economic growth. What we need for sustainable development, however, is not dichotomous thinking but harmony with nature. If nature is ingrained into peoples’ everyday life, citizens – not just a few environmentalists – would recognize nature’s significant value and strive to conserve it. Fortunately, Incheon has as a suitable environment as does Hong Kong, and citizens keen on the environment, such as our enthusiastic participants. Hopefully, in the future, Incheon can be a new model of sustainable development for cities all over the world.

To see more pictures, please visit our Flickr