OIE/FAO Network of expertise on animal influenza (OFFLU)

Situation Report and Guidance for H5N8 and other Eurasian H5 clade 2.3.4.4 Avian Influenza Viruses

29 November 2016

Wild birds play important roles in the circulation of avian influenza viruses and are reservoirs for low pathogenicity strains. In general, avian influenza viruses in wild birds can be transmitted to and from poultry, and potentially to and from other domestic animals and people. In order to reduce health risks to wildlife, domestic animals and people, it is important to understand all aspects of the circulation of the broad range of avian influenza viruses among susceptible populations: wild animals, domestic animals and humans.

Findings in 2014 – 2015

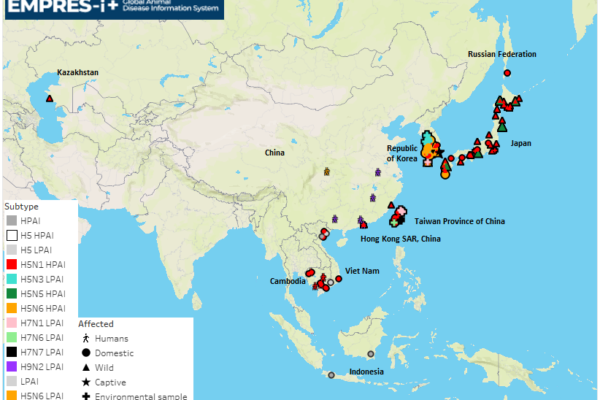

In early 2014, the People’s Republic of China, Japan and the Republic of Korea reported outbreaks of novel Eurasian (EA) H5N8-reassortant clade 2.3.4.4 viruses in migratory birds and domestic poultry. This H5N8 lineage of viruses has been characterized as highly pathogenic avian influenza in poultry (HPAI) and to date has not been reported to cause disease in humans or other mammalian species.

By November 2014, there were multiple reports of the H5N8 clade 2.3.4.4 in wild birds from South Korea, Japan, Russia, Germany, Netherlands, and North America. In several countries, the same viruses caused outbreaks in poultry.

Findings in 2016

In 2016, H5N8 outbreaks were reported from wild birds in March in Republic of Korea; in June in Russia; in November in India; in ten countries of Europe (Austria, Croatia, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Switzerland, Sweden, Finland and Netherlands) and two countries in the middle east (Israel and Iran) in November. Affected domestic animals include chickens, ducks, turkeys; and wild bird species include common pochard (Aythya ferina), tufted duck (Aythya fuligula), swans (Cygnus sp.), gull (Laridae sp.), common coot (Fulica atra), storks (Ciconiidae sp.), grey heron (Ardea cinerea), great crested grebe (Podiceps cristatus), black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus), common tern (Sterna hirundo), great cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo), painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala), pelican (Pelecanus sp.), munia bird (Lonchura), and other wild duck species (Anatidae sp.).

Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N6, a related virus that is also in the clade 2.3.4.4 that was previously found in China, Vietnam and Laos, was found for the first time in Republic of Korea and Japan from dead wild birds, captive animals (Japan only) and poultry (Korea only). It should be noted that this group of H5N6 viruses has been associated with human infection, including a number of deaths.

Further information regarding circulation of the EA-H5N8 clade 2.3.4.4 and subsequent reassortants will further improve understanding of the epidemiology for these unique viruses. Countries are urged to share findings from surveillance activities that can help fill in these gaps.

Wild Bird Movements

The majority of wild bird migration across Europe, Africa and Asia subsides in November for the winter season. While wintering locations of these migratory birds are often stable, additional movement within a region may be affected by local weather conditions, food resources, access to open water, etc.

Strategic wild-bird surveillance planning and enhanced messaging to poultry farmers to strengthen biosecurity practices before spring migration is warranted, especially if the virus persists over the winter in Europe, North America, and East Asia. Detections in indoor poultry farms where direct contact with wild birds has been considered negligible emphasizes indirect transmission to these production sectors from contaminated environments via fomites, further highlighting the ability of these viruses to persist in the natural environment.

Wild bird surveillance

In general, ongoing wild bird surveillance for avian influenza viruses is encouraged and may help fill gaps in knowledge about circulating influenza viruses. Based upon recent events, OFFLU recommends continuing and strengthening targeted wild bird surveillance activities in areas where EA-H5 clade 2.3.4.4 viruses have been detected and in other areas where there are significant populations of migratory waterfowl.

Currently these areas include Asia, Europe, Africa and the Middle East. Best practice guidelines established by FAO and OFFLU, including the FAO’s Manual on Wild Bird Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Surveillance and the OFFLU Strategy document for surveillance and monitoring of influenzas in animals can be consulted to aid in surveillance strategies and techniques.

There are several real-time RT-PCR protocols available for detection of EA-H5 clade

2.3.4.4 viruses and other avian influenza viruses.

http://www.offlu.net/fileadmin/home/en/resource-centre/pdf/Eurasian_H5_RRT-PCR.pdf

http://www.offlu.net/fileadmin/home/en/resource- centre/pdf/NRL_AI_PCR_NN_RTqPCR_N8.pdf

Options for collection of specimens from wild birds and further information on influenza diagnostics can be found on the OFFLU website.

For those conducting influenza surveillance activities, viruses should be characterized to at least the subtype level (H and N-type; see “Diagnostics” below); H5/H7 viruses should be characterized to pathotype. Full genome sequencing of wild bird avian influenza viruses is strongly recommended to further overall understanding of virus evolution. Information should be made available to the scientific community in a timely fashion through open access genetic databases.

The World Health Organization provides guidance and updates information regarding genetic alterations in animal influenza viruses that relate to increased virulence for humans to help inform public health risk assessment.

http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/Influenza_Summary_IRA_HA_int erface_10_03_2016.pdf?ua=1

http://www.who.int/influenza/human_animal_interface/avian_influenza/riskassessment_ AH5N8_201611/en/

OIE-FAO OFFLU recommends the following general practices for influenza A surveillance in wild birds:

- General Surveillance (routine or passive surveillance): Detection of AIVs, especially HPAIs, may occur through screening of wild birds received by diagnostic laboratories as part of surveillance programs in which all causes of morbidity and mortality are under investigation. Most often, passive surveillance is carried out on wild birds that are found

- Targeted Surveillance (active or risk-based surveillance): Targeted surveillance focuses on sampling according to specified criteria such as species, geographic location, and time of year and is most commonly conducted in apparently healthy live wild birds, but survey design may include sick birds, dead birds, and freshly- expelled bird feces. Sampling can be coordinated with other activities involving the handling of wild birds such as hunting or ringing/banding

- Sampling: Preferred sample collection includes oropharyngeal and cloacal swabs from live or recently dead birds (swabs from an individual bird may be pooled; but pooling of samples from multiple birds is not recommended), alternatively, fresh faeces may be collected. NOTE: where visual or photograph documentation of source species is not possible, DNA barcoding should be conducted when obtaining faecal samples. Collection of feathers may be useful; however, detection requires systemic circulation of the virus (presence of virus in follicle). While positive findings can be informative, negative results should be interpreted with caution as they may not accurately reflect the viral status of the bird. Basic epidemiological information (location [precise coordinates where possible], date of collection, species, sex, age, mortality or clinical signs of disease, and co-occurrence of disease in other species) should also be collected. More details are provided in FAO’s Manual on Wild Bird Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Surveillance and the OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals.

- Diagnostics: Several molecular assays for influenza A detection are available on the OFFLU website. Molecular detection of influenza A and subtyping assays may be followed by virus isolation procedures consistent with the OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. Viruses should be characterized to at least the subtype level (H and N-type) including cleavage site information. Full genome sequencing of wild bird avian influenza viruses is strongly recommended, when possible, to further understanding of overall virus evolution. More information is available on the OFFLU website at: http://www.offlu.net

- Reporting and Response: Any HPAI viruses from poultry or wild birds, and any H5/H7 LPAI viruses from poultry, are notifiable to OIE. LPAI H5/H7 and other low pathogenicity influenza A of wild birds can be notified on a voluntary basis using the platform WAHIS-Wild, which is separate from routine WAHIS or EMPRES-i. Additional relevant findings from surveillance for avian influenza viruses in wild birds should be reported to wildlife, domestic animal and public health authorities at the appropriate level. Detection of EA-H5 clade 2.3.4.4 or other avian influenza viruses in wild birds, including H5 and H7 subtypes, does not justify the imposition of trade restrictions or control measures in these

- Risk Communication: It is important that wildlife, veterinary, and public health authorities develop a coordinated risk communication strategy following positive surveillance findings. Since wild birds may serve as a reservoir for avian influenza viruses, it is expected that surveillance efforts will detect these viruses irrespective of any role wild birds may play in local epidemiological events involving poultry. Complete investigations must be carried out before attributing the source of avian influenza virus infection in poultry to wild birds. It is advisable to follow precautions to protect personnel conducting avian influenza surveillance under different scenarios (major die offs versus routine sampling of harvested birds) and guidance on what kind of investigations are needed when samples are

- Captive Wild Birds: Wild birds in captive collections are susceptible to infection with HPAI and LPAI viruses. Many countries require that all birds (wild or domestic) in a holding facility where HPAI is confirmed have to be culled. However, exceptions are possible for zoos or other facilities if a risk assessment is performed, daily clinical surveillance of all birds is guaranteed, a sampling plan is established and if the remaining birds are properly housed, so that contact with the possible source of infection is excluded and further spread is properly contained.

Role of epidemiological studies and research

Valuable information can be gathered through ongoing ecological, epidemiologic and molecular studies, as well as through other research to improve our understanding of the movement, maintenance, transmission and persistence of influenza viruses across the wildlife-domestic animal-human interface. OFFLU and STAR-IDAZ partnered to develop a global animal influenza research agenda and identified research priorities in avian (domestic and wild), swine, and equine species. Countries should collaborate in the effort to perform such studies and research, and to share data and results with the wider scientific community to improve local, regional and global knowledge. Joint investigations across sectors are important to gain improved knowledge of risk pathways, modes of spread and host range of influenza viruses.

Concerning Possible Activities in Response to Detection in Wildlife:

Following detection of HPAI viruses in wildlife, agencies should carefully consider response objectives, not only to minimize impacts of HPAI spread, but also to ensure that response actions do not inadvertently increase viral spread by disturbance of wildlife species or impact sensitive wetland environments through actions such as spraying of disinfectants. In all cases, responses should be based on current scientific understanding of the transmission and persistence of influenza viruses in wild birds and appropriately differentiated from mitigation actions that are employed in domestic settings.

Global consortium for H5N8:

The “Global Consortium for H5N8 and Related Influenza Viruses” was established for the global sharing of virus genetic data in real time, and to apply a “forensics” approach to trace back the evolutionary and epidemiological history of the viruses causing the outbreaks. Countries are encouraged to contribute virus sequences by contacting t.kuiken@erasmusmc.nl, mark.woolhouse@ed.ac.uk or martin.beer@fli.de. The consortium provides rapid feedback on the evolutionary relationships of national virus collections in the context of global virus emergence through http://virological.org.

FURTHER INFORMATION

OFFLUL: H5N8 inventory

EAAFP: How to battle bird flu? Saving wild birds, poultry and humans